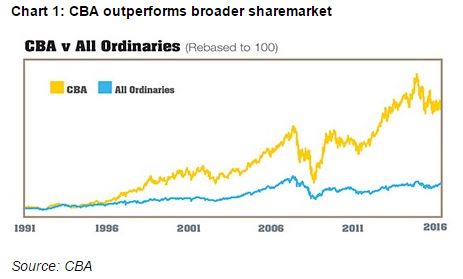

Early investors in privatisations, such as Commonwealth Bank, have enjoyed stellar gains.

Australian investors have been lucky to participate in the demutualisation and privatisation of a number of companies. Lucky because most demutualisations and privatisations have rewarded shareholders many times over. It has also helped boost the market capitalisation of the Australian sharemarket and has increased participation.

Many shareholders in demutualisations and privatisations are first-time shareholders. In fact, Australia has one of the highest rates of share ownership in the world, with 36 per cent of Australians holding shares directly or indirectly in 2014, according the ASX Share Ownership Study.

(Editor’s note: The Commonwealth Bank of Australia is a good example of the benefits of investing in privatisations for the long term. More than 800,000 Australian household own shares in CBA, which has just celebrated its 25th anniversary as a listed company on ASX. CBA listed on ASX on September 12, 1991 through the offer of 30 per cent of its shares to the public at $5.40 a share. The offer raised $1.3 billion and the closing price on CBA’s first day of trade was $6.46. A $2,160 investment in CBA during its initial public offering – 400 shares at the minimum subscription – is now worth $131,371 for those who reinvested their dividends. In its 25 years as a listed company, CBA has delivered a total shareholder return of 9,500 per cent and consistently paid out between 70 and 80 per cent of its profits as dividends.)

What demutualisation and privatisation means

Demutualisation is where a mutual organisation such as a building society becomes listed on the stock exchange, and there are a couple of key reasons why companies have gone down that path.

In the case of building societies, demutualisation used to be a condition before a banking licence could be pursued. For other financial companies, it was about transparency and competition. In the case of Colonial and National Mutual, a large part was about raising new capital.

NIB demutualised in 2007 and listed on ASX, becoming the first private health insurer on the market. At the time, NIB said it was pursuing demutualisation because of structural changes in the health insurance industry and to allow it to pursue acquisitions and opportunities in the sector.

Since then, Medibank Private has been privatised and there are now two private health insurers on the Australian sharemarket.

The Australian Securities Exchange itself is a result of a demutualisation in October 1998. The purpose was to broaden the membership base as well as providing a broader access to capital to fund growth and acquisitions. ASX shares began trading on October 14, 1998.

On the other hand, privatisation is when a government entity is sold to investors and is then traded on a stock exchange. The biggest privatisation in Australia has been Telstra, which was privatised over three tranches.

Telstra moved to privatisation after the opening of the telecommunications industry to competition in 1997. As such, it has been a more difficult investment proposition than other privatisations because of the effects of competition on the industry, Telstra’s share price and its business.

Best performers for members/shareholders

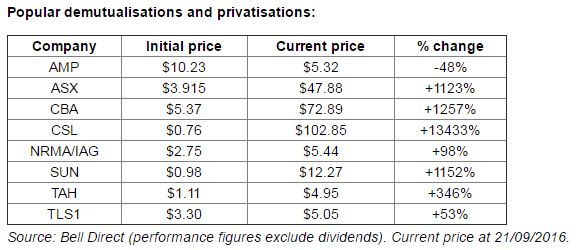

One of the top performers for shareholders has been CSL, a company with a 100-year history. Initially called The Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, it was established in 1916.

It originally floated at $2.30 per share in 1994 but given all the share buybacks the company has embarked on, the adjusted entry price is equivalent to around 76 cents. An initial $10,000 investment in CSL would now be worth over $1.3 million with more than $140,000 dividends paid in that time.

When things don’t go right: AMP/GIO

When AMP demutualised in 1998 it did so with an excess of capital. It soon went on a spending spree, picking up UK funds manager Henderson, National Provident Institution and then GIO. GIO was a $3-billion investment that saw AMP disastrously lose $1 billion. By 2003 its share price had hit a record low $2.72, having lost shareholders 73 per cent in value since listing.

With recent privatisations of QR National and Medibank Private, there are still opportunities for investors to participate in these types of investments. Like any investment, each opportunity should be assessed on its own merits.

Compared to initial public offerings, demutualisations and privatisations involve companies that have been around for decades. There is a track record of financial performance and in many cases the assets involved are difficult to replicate. In the investing world, we call this a moat, and companies with one tend to have less competitive pressures and an edge when it comes to selling their product.

Things to consider

Have you ever made an investment into a solid, good company, only to have the share price remain static for a number of years? Or seen a company announce a record profit, only to watch the shares fall? What is it that moves share prices? Often it is about understanding the catalysts for a business and whether it improves or worsens a company’s prospects.

Here are some questions to ask before making an investment:

- Is the company in growth phase or a more a mature income/cashflow-generating phase?

- What are the catalysts for the business and share price?

- What are the dynamics of the industry in which it participates? Is any structural or cyclical change occurring?

- Does the company have a moat?

- What the company is worth compared with what you are paying for the shares?

Overall, privatisations and demutualisations in Australia have rewarded long-term shareholders with stellar gains. However, it has not just been a winning proposition and like any investment, investors need to evaluate the risk and return in making the investment.

This article was first published on ASX website.